The Buddha Way Click for latest PDF 2022

A SUMMARY OF BASIC BUDDHIST TEACHING

In 1985 after coming in contact with the Sangha, the Buddha’s monastic order, I was sufficiently impressed to “turn for Refuge” and become a Buddhist. The monastics and lay people I met had all been influenced by the Theravada tradition of Southern Buddhism and the Venerable Ajahn Sumedho, an American who took ordination in Thailand and became a disciple of the Thai master Ajahn Chah. I have found Buddhist teaching and the practice of meditation both useful and inspiring and feel strongly that it has a tradition which has much to say that is relevant to our condition today. This paper was written recently (09) for a group of adults who were working with me to explore meditation and basic Buddhist teaching.

The Way of the Buddha

A short introduction

For a long time Buddhism has been seen as a religion of the exotic and mysterious East, and to an extent it still is. However, since the 19th Century there has been a slow but steady increase in the number of people in Britain, Europe and America who have been drawn to it. This has not happened very much with other religions that have come here. They have largely remained within the immigrant communities. Buddhism in Britain however is different for while a significant number of Thai, Sri Lankan , Tibetan, Japanese and Chinese Buddhists have settled here, a substantial and steadily growing number of Westerners have adopted Buddhist practice and teaching. According to the 2011 census there are 238,626 Buddhists in England. In 2001 Buddhism constituted 0.3% of the population of England, which increased to 0.5% in the 2011 census.

The reasons Western people find the Buddhist Way attractive are various, ranging from disillusion with elements of contemporary religious or secular culture to a desire to be “alternative” and different, but for many like me it is simply because we have found the practice and teachings of the Buddha Way tie in with what we already value and we find they make sense. We have found that not only is it helpful in coping with the challenges and pressures of contemporary life and the quirks of our own personalities, but it is a useful “roadmap” and a challenging pointer to living better. As such it can be a source of joy, calm, and happiness which leads us to new insights about ourselves and the way things are. Certainly also it can give us a heightened experience of what I can only be describe as transcendence.

It has also been important for me that this path requires no “leaps of faith.” I am not expected or required to go against what I see as rational, in fact quite the opposite. Nor am I expected to believe or disbelieve in any god or accept any miracle stories as reports of “real, historical and yet supernatural events.” Neither is there an expectation that I should accept texts, teachings or authorities uncritically. Instead the Way of the Buddha commends and provides training in the calm, rational examination and contemplation into the way we actually are (insight meditation).It also commends generosity, compassion and the living of a consistent, responsible moral life as the foundation for happiness.

All this is based on the teaching and system of mental and moral training developed by its founder Sidhattha Gotama and embodied in the community he trained and set up. He lived in Northern India some four centuries before the start of Christianity (exact dating is not possible) and he is usually known as the Buddha.

Sidhattha is his personal name, Gotama his family name. He is also called Sakyamuni which means sage or wise teacher of the Sakya people, the tribal group he belonged to. The Buddha is a title, which means the enlightened one, the awakened one or the one who knows that is he who knows the truth, the way things are. This truth is referred to as the Dhamma, the Teaching.

According to this teaching then, the Buddha is regarded not as a prophet or spokesman for the divine, or divine himself, but rather as a realised, enlightened and exceptionally wise human being. It is also not claimed that he is the only one, rather that in the course of human history there have been others, both men and women, who deserved to be so described, but it is claimed that Sidhattha is particularly significant for us at this time, so he is usually spoken of as The Buddha, the fully enlightened one.

Unlike what developed in Christianity and Islam, the story of the Buddha Sidhattha’s life was only committed to writing and used as a teaching tool centuries after his death. What has always been seen as central however, is not the story of his life, but the efficacy of the system of spiritual training he developed and the community of those who live by it which he inaugurated. Still the story of his life has always worked as a very effective teaching tool to illustrate his teaching.

Outline of Sidhattha’s Life story:

He was born a member of the noble shatriya warrior ruling caste in Lumbini in Nepal and brought up in Kapilavatthu. This was a small state which his father ruled. The traditional date given for his birth is 543 BCE. Some scholars estimate he was born around 368 BCE. Many others prefer 483 BCE. There is no archaeological evidence for these dates but the pillars erected by Ashoka, first Emperor of India and himself a Buddhist, have been dated as erected around 268 BCE. These show the Way of the Buddha was well established by then. Some of these pillars can be seen today in the British Museum, others still stand in India.

The story as traditionally told certainly contains symbolic and mythical elements. Predictions about his future, his conception, birth and the immediate death of his mother have this quality. This also applies to elements in the story of his marriage to the princess Yasodara when sixteen and his fathering of a son, Rahula.

DISEASE, OLD AGE AND DEATH

There is then the powerfully dramatic story of how the young prince, provided with every luxury of wealth, family support and pleasure, is confronted by the inescapable realities of disease, old age and death when travelling around his father’s domain. As a result he decides he must renounce his privileges, leaves his wife and child in the care of his family, and sets off with nothing but the ragged robe of a religious mendicant (a samana, such world renouncing spiritual seekers were then common in India) to seek enlightenment as to how to deal with what he thinks of as this unsatisfactory human condition.

After years exploring the philosophical teachings and meditation practices of several leading Indian holy men, he so over-does the fasting and ascetic practice that he is reduced to a skeleton and is about to collapse and die of starvation. Five other ascetics with him are very impressed by his dedication and prepare to see him realise enlightenment as a result of such exemplary mortification, but he recognises that what he has done has got him no-where so when a passing girl offers him some food, he accepts. The others, disgusted at what they see as his weakness, leave him and go off to Benares, but he remains and when he has regained his health, he resolves to sit beneath a fig tree, the bodhi tree. There he has an overwhelming experience which he describes as his Enlightenment. He is 36.

He then sets off for the Deer Park in Benares where he again meets the five who rejected him. As he approaches they recognise he is transformed, ask him to address them, which he does, preaching his first sermon. Immediately they become his disciples.

With their support he then sets about organising these samanas ( renunciate spiritual seekers, something that was quite common in India then as now) into a disciplined community who are supported by lay followers or householders. Setting up such an Order is something no one has ever done before. This Order becomes known as the Bhikkhu (one who lives on alms) Sangha (community).

Over the next 44 years the Buddha travels around the country building up his disciples and fine-tuning their training rules known as the Vinaya until the Sangha become a very carefully organised self-disciplining community with hundreds of monks who wander across the country and settle down together during the monsoon on land given to them by their lay supporters. The Sangha is not however exclusive for he declares his teaching is open and for everyone and that any man, regardless of rank, caste or background may enter to train and work towards liberation/awakening. As a result the Order and the circle of its lay supporters grows steadily. He calls his teaching and training The Middle Way for he sees it as neither self-indulgently lax nor guiltily self-punishing, but calm, joyful and balanced. He also visits his father and his court, and accepts his son Rahula into the Sangha. He also acts as a spiritual guide to a wide range of very different people, kings and rulers, the followers of other religious teachers, rich merchants and poor peasants, men and women. He sees them regardless of caste or rank and they include a well-known courtesan and a notorious murderer.

After initial reluctance he succumbs to pressure from his mother-in-law who wishes to enter the Sangha along with several other women from the court. For them he founds a special order, the Bhikkhuni Sangha.

He also resists attempts by some to take over control of the Sangha and to get him to appoint a successor. Instead he makes sure his teaching and the Vinaya is well understood and the Sangha set up to be self-regulating without an overall leader. Finally he dies at the age of eighty with the rules governing the Sangha clearly defined and in operation and his teachings widely disseminated across India, memorised by his disciples, and recited communally.

After his death wandering bhikkhus and merchants carried his teaching and system of training, across India, North into Afghanistan and Tibet, then to Mongolia and China, (East along the Silk Road and West perhaps to Syria).It then spread from China to Korea and from Korea to Japan, and from China to Vietnam. Over time variations and schools developed and this Northern tradition became known as the Mahayana (The Broad Way).

The Buddhist community also expanded south, going from India to Sri Lanka, to Thailand and Burma, Cambodia, Laos and again Vietnam. Priding themselves on keeping as close as they could to what they had originally learnt, this tradition is seen as more conservative and is known as the Way of the Elders, the Theravada. Most scholars consider that in its practice and in its preservation of the Pali scriptures it has remained pretty close to what the Buddha originally taught. For this reason I have been inclined to stick with this tradition.

What is it all about?

The Buddha said, “I teach only the cause and cure of human suffering/disease/alienation.” The Way or Path (Magga) of the Buddha to achieve this is a set of teachings to be investigated and reflected on and a system of moral training rules. These are set out in three forms.

For householders, that is men and women living and working singly or in families, there are five basic precepts or rules of moral guidance.

For those who intend to spend a limited amount of time training in the viharas or monasteries, these are expanded to either eight or ten basic rules, and those who undertake the extremely arduous and demanding training of a Bhikkhu train to live by the 227 rules of the Pattimokkha.

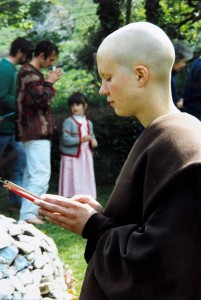

“Going Forth” . A Bhikkhu takes ordination at Chithurst Forest Monastery

These are not commandments seen as moral absolutes, but elements in a training regime which people are invited to reflect on and adopt when and if they are ready and when they see the sense in them. The aim is to train the mind and the emotions in order to reduce suffering for oneself and others, to experience deeper happiness, and to achieve deeper insight so one might live more in harmony with one’s own nature and the way things actually are in the world.

The Buddha’s system of training is built on three basic elements which apply to all the regimes from the Five Precepts of the householder to the Patimokkha of the Bhikkhu. These elements are:

Dana – Generosity, the giving of time, attention, skills and requisites.(To the poor and the needy, to one’s family and dependents, in the practice of hospitality and in giving food and practical support to the renunciate community, the monastic Sangha.)

Sila – Restraint and moral discipline based on respect for all beings capable of suffering.

Bhavana – Mental Training – meditation and the development of insight into the human condition.

Those who choose to enter the Buddhist Sasana or sphere of influence often express their commitment by taking part in a simple ceremony in which they Turn for Refuge. In this they simply state they will turn for help and protection to The Buddha, The Dhamma, and the Sangha.

Turning for Refuge to the Buddha is to turn to the enlightening mind, that open awareness which the Buddha exemplified in himself, but also that awareness or “Buddha Nature” to be found in all of us, so it is an acknowledgment of that which is best within us and what is special about being human.

Turning for Refuge to the Dhamma, the Teaching or the Truth is to turn towards and explore the Buddha’s teaching, but also explore everything which points to the reality of who we are and where we stand be it psychology or nuclear physics.

Turning for Refuge to the Sangha.Primarily this is seen as the Community of those who live by that teaching and usually refers to the Bhikkhu Sangha, or the renunciate community. Today that also includes the Women’s Order of Siladara which has been set up here in Britain, the original Bhikkuni Order having died out centuries ago. However, since Sangha simply means Community, there is a sense in which it also applies to all whose good, generous and realistic behaviour contributes towards the happiness of the wider human community.

Looked at a little differently as was shown to me while on a retreat lead by the Buddhist nun Ajahn Candasiri, I was shown that Buddha, Dhamma and Sangha are interrelated, even interlocked. As human beings we have the privilege through our senses and our brains to grow in an awareness of ourselves and all around us which provides us with the ability to think about and explore reality, the way things are, the truth about life, death and the universe. Based on this capacity to grasp something of the truth we are able to relate to each other as a compassionate, mutually supportive community, be it family, religious community, nation or the wider human community. Buddha, Dhamma, Sangha can thus be seen as Awareness, Truth, Community.

For the Buddhist householder or lay person turning for refuge means something quite practical, undertaking to practice and work out in one’s life the five basic training rules or precepts (sila) testing the truth of them for oneself. (ehipassiko)So what are these?

The Five Precepts.

1. To undertake the training rule of turning away from destroying living beings capable of suffering. (Put positively, respect for life, human and animal, respect for the environment and an aversion to violent solutions as unskilful.)

2. To undertake the training rule of turning away from taking what is not given.(Put positively, respect for the property and work of others, being honest and non-exploitive.)

3. To undertake the training rule of turning away from the irresponsible misuse of the senses and sexuality. (Put positively responsible and faithful relationships, including fidelity in marriage)

4. To undertake the training rule of turning away from lying and abusive language (put positively honesty and sensitivity in speech).

5. To undertake the training rule of turning away from drink and drugs which cloud the mind and lead to behaviour which ignores consequences. (Put positively mindful and responsible behaviour)

How one uses and practices these precepts in the context of life in society is recognised as being something each person needs to reflect on and decide for oneself. Some take them very literally; some seek to apply them in terms of underlying principles. The result is continuing debate over issues such as pacifism, vegetarianism, euthanasia and abortion.

The Teaching.

As we have noted the Buddha emphasised his teaching is not there to be believed in or taken on faith, but tested in the light of personal experience and reflection, in the context of practising the training rules of a basic moral life, that is a life which does not intentionally cause others suffering. This can be either as a layperson or as a member of the Sangha. It is also emphasised that if one attempts to examine the teaching or to undertake meditation without at least a commitment to follow the spirit of the five precepts and live a considerate moral life, one is likely, given our unstable natures, to make serious mistakes in understanding what is important.

Without adopting these training rules, human life is characterised by avijja, delusion, misperceptions, ignorance, – we get things wrong, we misunderstand, we kid ourselves, we give in to our fantasies which results in unbalanced craving or tanha, that is in greed and hate. On the other hand if the training rules are adopted and worked at, it is asserted that we can move towards not a mere intellectual understanding, but an actual realisation of, a direct knowledge of the heart of the Buddha’s teaching which he called: The Four Noble or Ennobling Truths. He called the truths Noble to emphasise that true nobility has nothing to do with caste (varna), social status or wealth..

The Buddha’s analysis of who we are “leads me to see I am not a fixed essence, but an interactive cluster of processes.” (Batchelor)

The Four Noble Truths. Or the four points that ennoble those who recognise them. .

- All Life is characterised by Dukkha,. a quality of unsatisfactoriness, alienation, anguish, mental and physical pain and suffering. What is more life is impermanent Anicca. Nothing and no-one remains the same. We scrabble around in the face of uncertainty, uncertainty in relationships, in fact uncertainty in everything we do and experience – yet we crave certainty, stability and permanence.

This dukkha consists of all forms of mental and physical suffering and anguish, and that sense of loss and unhappiness brought about by change, and that underlying and exacerbating this is a misunderstanding or misperception of what constitutes our basic identity, what we call our self. “But what is the self?” the Buddha asked. The Buddha’s analysis was that what we call our self can on reflection be broken down into five elements which roughly translated are:

1.Matter – our bodies – where do they begin or end and everything about them is fragile and changing.

2.Feeling, what we touch, taste, hear, smell, see, all our physical and mental sensations.All changing

3.Our Perceptions, that is our emotional reactions arising out of these – delight, desire, pleasure, pain, boredom. All changing.

4.Our Mental Formations or patterns of action. Our habitual ways of thinking, reacting and carrying on which bring about good, bad or neutral consequences. All changing.

5.Our interconnected Consciousness of all these things. This again lurches about, moment by moment, easily distracted and missing the point. Always changing.

The point as I see it is however really quite simple and not dependent on a total understanding or acceptance of this quite complex analysis with its unfamiliar categories. It is this. However we analyse the elements out of which we are made, be they mental, physical, or cultural, we are lead to conclude that they are all in a constant state of flux, and since everything about us is constantly changing, the reality is we and all we experience is, as the Buddha said,“Anatta, not self.”

To describe this he used the analogy that our reality is like that of a flickering flame or a swirling whirlpool. Instead we erroneously imagine ourselves as having an essential unchanging essence and identity, an atomistic individuality, that there is a clear boundary between what is me and what is not me, and that this identity is based on our having an indestructible individual soul. Indian religions called this the atman, and Christianity and Islam similarly speak of us as having a soul or spirit. The Buddha’s denial of this teaching and his assertion that we are essentially a bundle of ever changing elements was and is quite revolutionary in the development of our understanding of human consciousness and is something contemporary philosophers and psychologists are currently exploring.

2. The cause of Dukkha then is Thirst or Desire, Tanha,Thirst for sense pleasures, (food, drink, sex, excitement) thirst for becoming, achievement, (may I be powerful, may I be rich, may I be loved and recognised) and thirst for self-destruction. (I hate myself, I wish I was dead, I hate the way I am) Thirst or desire then can be either aquisitive – “I desire this, I crave that,” or negative, “I can’t bear this, I hate that, I hate myself.” It can also be both, “I hate you and I want you,” the good old love-hate relationship.

3. There is however the possibility of emancipation from, of liberation from Dukkha in its many forms, and the key to this is to learn to eliminate thirst, tanha, not by denying it or attempting distraction, but by facing it and reflecting upon it and so finally to reach a state of transcendent peacefulness, Nirvana.

4.The way to Nirvana is to follow the Path.

Obviously Nirvana is not a place but a state and the tradition teaches that the Buddha attained it from the time of his Enlightenment or Awakening. It is also something which is extremely elusive and according to the tradition, hard or impossible to express in words.

Claims that anyone can or has achieved a state of perfect wisdom and moral purity will strike many, including myself, as inherently implausible.(note similar claims are made for Jesus and Mohammad) Perhaps such a cynical reaction as this may be because I still have such a long way to go. On the other hand what is obvious and plausible ( because we do come across such people, often in the most unpredictable and unlikely situations) is that some human beings even if not “perfect” are much more enlightened, wise, good, compassionate, focused, sensitive and admirable than others and that recognising this and working to become more aware and mindful about ourselves and the way things are is definitely worth pursuing.

Perhaps, as with any journey, it is what is encountered, experienced and learnt on the way that is as important as the destination.

So the Buddha commends us to use the teaching and training he provided, be it for some as renunciates in the Sangha or for many as lay householders, to follow a path in our lives which will lead us towards increasing awareness/enlightenment and away from misery ignorance and suffering. This will of course be a gradual and life-long journey.

the Noble Eightfold Pathof Wisdom, (panna) Ethical Conduct,(sila) and Mental Training (Samadhi)

1. Right Understanding (Panna wisdom) A deep realisation of the teaching as seen above in the enobling truths.

2. Right habits of Thinking, above all compassion and love mettha towards ourselves and all around us.) Panna

3. Right Speaking. (Sila ethical conduct) Truthful, peaceful, avoiding anger and dissension.

4. Right Action. ( Sila) Behaviour which expresses harmlessness and generosity.

5. Right Livelihood (Sila) Adopting a way of life that is non-exploitive, non-harming, honest, avoiding violence.

6. Right Effort. (Samadhi mental discipline) Disciplined, systematic, persistent.

7. Right Mindfulness. (Samadhi), The awareness that leads to compassionate, understanding, sympathy, kindness.

8. Right Concentration.(Samadhi) The systematic development of a stable, not distracted quality of mind through the practice of meditation and wise reflection.

The Buddhist community then is made up of Householders and the Samana community of spiritual renunciates, centred upon the Bhikkhu Sangha and now in the West the small Siladara community. They undertake the extremely demanding regime of living by the 273 training rules of the Pattimokha, the monastic rule. (The Siladara follow a similar rule)The Samana Community then lead by their example which influences the whole Buddhist sphere of influence, and dedicate themselves to be a living embodiment of the Buddha’s Way “for the good of the many and for the healing of the world.”

The Samana community in the Theravaden tradition considers the Buddha laid down in the Vinaya that it is forbidden from providing for itself. This means it is dependent for its continued existence and for all the necessities of life upon the wider circle of householders or lay supporters who give freely to support the Samanas, most dramatically in the daily offering to them of food. (dana) In return for this, which is seen as an opportunity for householders to diminish selfishness and practice generosity, the Samanas offer teaching, counselling and often education in return. In those countries where the monastic Sangha is strong it plays an important part in the socialising, general education and moral training of young men who often spend a period of time, anything from some months to some years, living under the direction of the bhikkhus and in accordance with the ten basic rules of monastic practice (Samanera ordination).They are free to return to householder life, which they usually do.

Those who undertake the more demanding and minutely prescribed Bhikkhu (or Siladara) ordination “go forth” for an indefinite period or for life and are treated as novices and accept the direction of a senior for at least five years. They own nothing but robes, bowl and medicines and live lives of complete celibacy. After they are considered trained and stable they are free to move off, travel, or go to another monastery of their choice.They too though are free to disrobe and return to householder life at any time.

This is true for all Samanas, but some dedicate their whole lives to living according to the renunciate Vinaya or code of conduct, while others, some who are married with families, will simply spend a period of time within a monastery as Samaneras before returning to them.

The monastery or temple (vihara) is a place for the practice and study of the Buddha’s teaching and in particular for the practice of disciplined reflection or meditation and for Dhamma study in the context of what is an extremely carefully prescribed life-style.

Meditation or “sitting” is something which needs to be learnt in a group. It has to be done or practiced. Reading about it on your own hardly ever makes much sense. In its essence it is the discipline of learning to focus on the present moment by using the breath and the body to reflect upon the changing sensations, thoughts and emotions which make up our consciousness. Doing this heightens our awareness and enables us to discern and let go of those desires and aversions which make for destructive thinking and behaviour. As such the value of meditation training is something which is useful and harmonising to all who come in contact with it and learn in some measure to practice mindfulness, not just in a monastic context, but in all areas of our lives.

The Buddhist Path and language.

The Buddhist tradition with its teachings, scriptures and training regime has been preserved and transmitted through the unbroken succession down the centuries of the renunciate community, the Sangha who also memorised and recited the Buddhist scriptures before they were written down. For the Theravada this is in the ancient North Indian language known as Pali, a tongue the Buddha may have spoken.

The Pattimokha (the key summary of the monastic rule, the Vinaya,) is recited communally twice a month (it takes about an hour and a half to do so) and it is to be found throughout the Buddhist world, including the Mahayana traditions (although they modify and use it in slightly different ways from the Theravadins allowing monasteries to be self-supporting) so there is good reason to believe that it remains in essence as it was originally developed during the long life of Sidhattha Gautama himself. Interestingly it only prescribes rules for monastic behaviour and nothing about belief.

The Buddhist scriptures are extremely extensive in the Pali Canon. Divided into three “baskets” or Tipitaka they consist of the Vinaya Pitaka which contains all the rules and explains the discipline of the Sangha, the Sutta Pitaka which consists of a very large collection of the Buddha’s sermons and religious poetry and the Abidhamma Pitaka which explores the Buddhist philosophy of mind. This means the basic elements of the teaching are to be found in many places but always add up to much the same thing. There is little argument in Buddhist circles as to what those basic elements are, though there are differences of emphasis.

Translating Pali words and concepts into English makes one aware of how complex and slippery translation can be when dealing with a different culture and a different time because words have associations and resonances which are time and culture specific. Terms like monastery, temple, monk, suffering, insight, etc all have meanings in English which only approximate the meaning of the ancient Pali originals. Even the word Buddhism is an English word which can be misleading as a way of describing a religion which is not based on a set of beliefs which are accepted “on faith”, but on adopting a way, a path, and a pattern of training rules for behaviour which are seen by each person to be true for themselves.

The Buddhist attitude towards other religions is based on a recognition that all our beliefs about what we think is true are necessarily seen from an individual perspective. What is more there is a recognition that all language is elusive and can be understood by different people in different ways. This means recognising that while a certain uniformity as regards practice is possible across a group it is impossible as regards beliefs so Buddhists try to follow the Buddha’s example and advocate tolerance and a positive appreciation of the religions, points of view and ways of life of others. Buddhists are prepared to recognise wisdom and good teaching, compassion and generosity wherever it is to be found. Buddhists are happy to engage in dialogue and do not engage in aggressive proselytising.

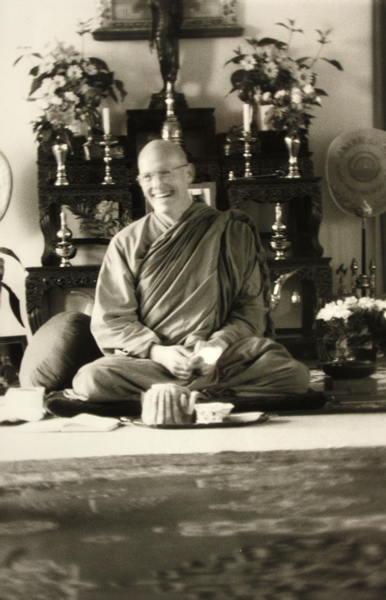

Tan Ajahn Sumedho at Amaravati Buddhist Monastery

The Buddhist focus on personal practice and intention may appear self-centred or otherworldly, but its purpose is “for the good of the many and the salvation or healing of the world.” And our starting point has to be developing our own awareness. Certainly wherever the Buddhist traditionit has taken root either in its Mahayana or Theravada forms it has deeply influenced the local cultures and in general promotes respect for persons regardless of rank, race, sex or caste, religious tolerance and humane, moral and generous behaviour together with respect for animals and the environment.

It is the first religion to spread across very different racial, cultural, linguistic and political boundaries and it was certainly the most widely practiced world religion until the explosion of Islam and the later global spread of Christianity. It also has never been imposed on people or spread by war. Signs are that this religion which almost alone proudly claims to be entirely man made is far from finished.

John Baxter

Google now is of course a fantastic source of information.See:

Buddhism.

The Buddha,

Ajahn Sumedho,Ajahn Chah.

Zen Buddhism,

Tibetan Buddhism,The Dalia Lama etc etc. Wikipedia. Etc.

The Devon monasterywww.hartridgemonastery.org

Some good books:

What the Buddha Taught by Dr Walpola Rahula (a brilliant, key text by a great Sri Lankan scholar monk.)

Therevada Buddhism by Richard Gombrich, Professor of Sanskrit, Oxford University.

An Introduction to Buddhism by Peter Harvey, Professor of Buddhist Studies, University of Sunderland

Buddhism.A very short Introduction by Damien Keown, Professor of Buddhist Ethics, Goldsmiths College, University of London.

Wherever you go, there you are.Mindfulness Meditation for Everyday Life by Dr Jon Kabat-Zin. A guide to meditation by a distinguished American doctor.

Consciousness.A Very Short Introduction. Susan Blackmore.Oxford University Press. A psychologist who specialises in the study of Consciousness.Examines how the Buddha’s teaching on not self accords with contemporary scientific investigations into the mystery of consciousness.

Buddhism Without Beliefs by Stephen Batchelor. Bloomsbury. The work of a distinguished former Zen monk and scholar.

What the Buddha Thought by Richard Gombrich. 2009 Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies. This scholarly study is a very important work in which Professor Gombrich shows how the Buddha modified or rejected the teachings of contempoary Indian gurus. He also argues that the Pali scriptures of the Theravaden tradition are generally reliable in providing us with a record of the Buddha’s teaching and concludes that the Buddha was both brilliant and original. This is not however the first book one should read on the subject.

Like to look at some pictures of the Buddha Way taking root in England? Go to my Art and Images blog http://www.getshot.co.uk/wow/the-buddha-way-in-england/#more-1374

Books can only take you so far, and meditation is almost impossible for most of us without starting in a group. Sooner or later you need to meet up with others interested in or practicing the Buddha Way.

E mail john@nulljohnbaxter.org

Ajahn Sumedho

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to: navigation, search

|

Ajahn Sumedho |

|

| Pictured (left) with a visiting Thai monk | |

|

Born |

Robert Jackman July 27, 1934 (Age: 76 years) Seattle, Washington, USA |

|

Occupation |

Buddhist teacher |

|

Title |

Luang Por Ajahn Sumedho |

|

Predecessor |

Ajahn Chah |

|

Religion |

Theravada Buddhism |

Luang Por Ajahn Sumedho (Thai: อาจารย์สุเมโธ) (born Robert Jackman, July 27, 1934, Seattle) is the senior Western representative of the Thai forest tradition of Theravada Buddhism. He has been abbot of Amaravati Buddhist Monastery just north of London since its consecration in 1984. Luang Por means Venerable Father (หลวงพ่อ), an honorific and term of affection in keeping with Thai custom; ajahn means teacher. A bhikkhu for 43 years, Sumedho is considered a seminal figure in the transmission of the Buddha’s teachings to the West.

| Contents |

[hide]

[edit] Biography

Sumedho was born Robert Jackman in Seattle, Washington in 1934[1][2]. During the Korean War he did military service for four years from the age of 18 as a United States navy medic. He then did a BA in Far Eastern studies and graduated in 1963 with an MA in South Asian studies at the University of California, Berkeley. After a year as a Red Cross social worker, Jackman served with the Peace Corps in Borneo from 1964 to 1966 as an English teacher. In 1966 he became a novice or samanera at Wat Sri Saket in Nong Khai, northeast Thailand. He took profession as a bhikkhu in May the following year.

From 1967-77 at Wat Nong Pa Pong, trained under Ajahn Chah. He has come to be regarded as the latter’s most influential Western disciple. In 1975 he helped to establish and became the first abbot of the International Monastery, Wat Pa Nanachat in northeast Thailand founded by Ajahn Chah for training his non-Thai students. In 1977, Ajahn Sumedho accompanied Ajahn Chah on a visit to England. After observing a keen interest in Buddhism among Westerners, Ajahn Chah encouraged Ajahn Sumedho to remain in England for the purpose of establishing a branch monastery in the UK. This became Cittaviveka Forest Monastery in West Sussex.

Ajahn Sumedho was granted authority to ordain others as monks shortly after he established Cittaviveka Forest Monastery. He then established a ten precept ordination lineage for women, “Siladhara“.

Ajahn Sumedho was the abbot of Amaravati Buddhist Monastery near Hemel Hempstead in England, which was established in 1984. It is part of the network of monasteries and Buddhist centres in the lineage of Ajahn Chah, which now extends across the world, from Thailand, New Zealand and Australia, to Europe, Canada and the United States. Ajahn Sumedho has played an instrumental role in building this international monastic community and he has now retired to live in a monastery in Thailand.

Sumedho’s retirement was announced in February 2010. His successor is the English monk Ajahn Amaro, hitherto co-abbot of the Abhayagiri branch monastery in California‘s Redwood Valley.[3]

[edit] Teachings

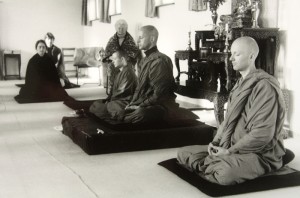

Sumedho (seated beneath the altar) in conversation with a bhikkhu, just before Amaravati’s daily meal

Ajahn Sumedho is a prominent figure in the Thai Forest Tradition. His teachings are very direct, practical, simple, and down to earth. In his talks and sermons he stresses the quality of immediate intuitive awareness and the integration of this kind of awareness into daily life. Like most teachers in the Forest Tradition, Ajahn Sumedho tends to avoid intellectual abstractions of the Buddhist teachings and focuses almost exclusively on their practical applications, that is, developing wisdom and compassion in daily life. His most consistent advice can be paraphrased as to see things the way that they actually are rather than the way that we want or don’t want them to be (“Right now, it’s like this…”). He is known for his engaging and witty communication style, in which he challenges his listeners to practice and see for themselves. Students have noted that he engages his hearers with an infectious sense of humor, suffused with much loving kindness, often weaving amusing anecdotes from his experiences as a monk into his talks on meditation practice and how to experience life (“Everything belongs”).

[edit] Sound of Silence

A meditation technique taught and used by Ajahn Sumedho involves resting in what he calls “The Sound of Silence”[4]. He talks at length about this technique in one his books titled “The Way It Is”[5]. Ajahn Sumedho said that he was directly influenced by Edward Salim Michael‘s book : The way of inner vigilance (republished in 2010 with the new title : the Law of attention, Nada Yoga and the way of inner vigilance” and for which Ajahn Sumedho wrote a preface).

The “Sound of Silence” is also the title of one of Ajahn Sumedho’s books (published by Wisdom in 2007). In his book, the “Sound of Silence,” he mentions that it was not directly influenced by his study of Ven. Hsu Yun‘s works or by the Shurangama Sutra, though he has heard that the Shurangama mentions a similar practice.

[edit] See also